🧭 Introduction

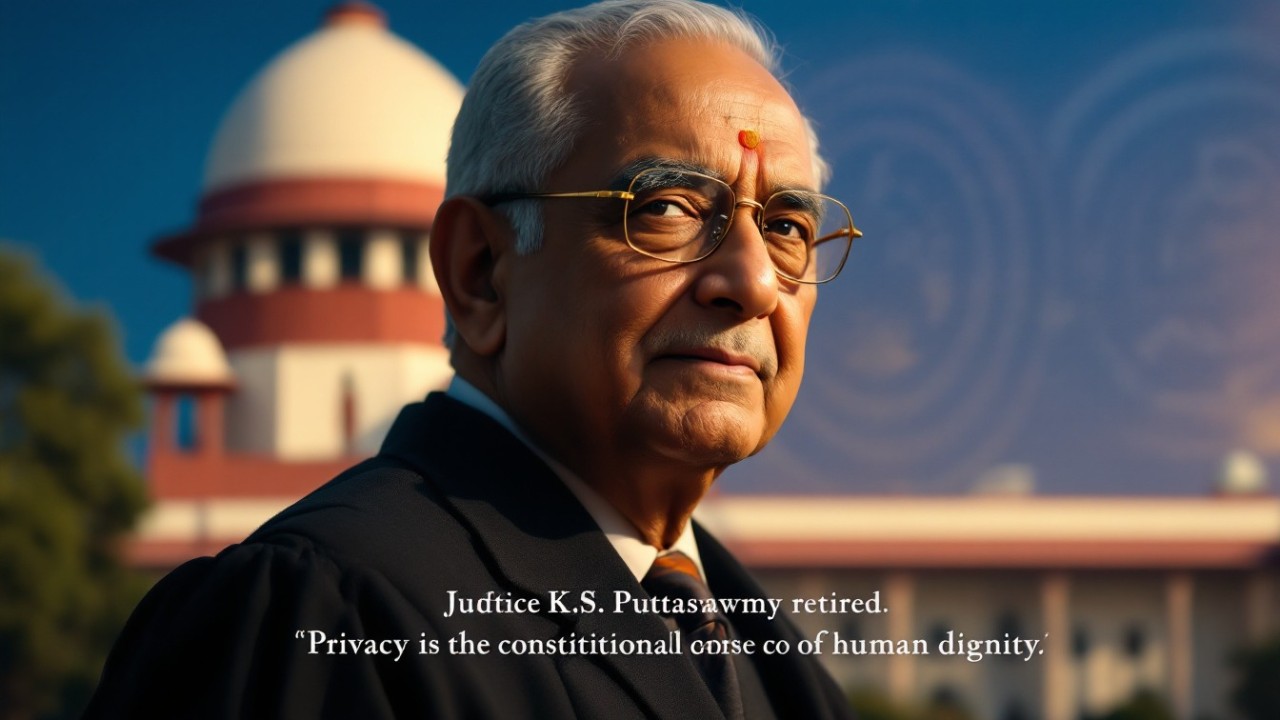

In an age where technology governs everything—from our identities and finances to our personal choices—the debate over individual privacy has become both inevitable and urgent. The 2017 judgment in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) & Ors. v. Union of India was not just a legal milestone—it was a constitutional awakening.

It answered a fundamental question:

Does the Indian Constitution guarantee every citizen a right to privacy in the digital and physical realms of life?

The answer was a resounding yes, delivered by a unanimous 9-judge bench of the Supreme Court, restoring faith in the transformative power of the Indian Constitution.

🏛️ Background: How Aadhaar Triggered a Constitutional Crisis

The Aadhaar scheme, introduced by the Government of India in 2009, was envisioned as a digital identity system to streamline welfare benefits and services. But over time, the UIDAI project became controversial due to:

- Mandatory biometric data collection

- Linking Aadhaar to essential services like PDS, pensions, bank accounts, and mobile numbers

- Exclusion of vulnerable populations due to technical or documentation issues

- Fears of mass surveillance and data misuse

Multiple petitions were filed challenging Aadhaar’s validity and its infringement on personal liberty. But a preliminary hurdle had to be cleared first:

Is privacy even a fundamental right under the Constitution?

This question reached the Supreme Court and demanded a Constitution Bench to reconsider outdated precedents from 1954 and 1962.

⚖️ The Core Legal Issue

Whether the Right to Privacy is a fundamental right protected under Part III of the Indian Constitution?

Earlier, in:

- M.P. Sharma v. Satish Chandra (1954) – The SC held that privacy was not protected under Article 20(3).

- Kharak Singh v. State of UP (1962) – Privacy was partly recognised but not fully embraced.

Both cases failed to fully acknowledge the autonomy and dignity of individuals as protected constitutional values.

👩⚖️ Verdict: A Unanimous Reaffirmation of Human Dignity

On 24 August 2017, the Supreme Court delivered a landmark judgment, declaring:

✅ The Right to Privacy is a Fundamental Right, protected under:

- Article 21 – Right to life and personal liberty

- Article 19 – Freedom of speech, association, and movement

- Article 14 – Equality and protection from arbitrary state action

✅ The previous rulings in M.P. Sharma and Kharak Singh were overruled

✅ The Court provided a broad, multidimensional framework of privacy, applicable to:

- Data and digital privacy

- Physical autonomy

- Decisional privacy (choices in relationships, reproduction, faith, lifestyle)

“Privacy is not lost or surrendered merely because the individual is in a public place.” — Justice D.Y. Chandrachud

🔍 Three Dimensions of Privacy Recognised

- Bodily Privacy – Protection from invasive procedures and physical coercion

- Informational Privacy – Control over personal data, identity, and digital presence

- Decisional Autonomy – Freedom to make personal choices (e.g., marriage, sexual orientation, procreation)

This judgment provided a constitutional shield to citizens against both state surveillance and private data exploitation.

🌐 Precursor Role of High Courts

Before this case was elevated to the Supreme Court, several High Courts flagged critical privacy concerns:

- Kerala High Court questioned biometric schemes in welfare projects

- Delhi High Court expressed concern over Aadhaar's misuse in education and mobile authentication

- Bombay & Karnataka High Courts saw petitions on Aadhaar and fundamental rights

These early warnings formed the judicial groundwork that inspired the Puttaswamy petition.

📈 Impact and Legacy of the Judgment

🧠 1. Catalyst for Future Progressive Rulings

This ruling laid the foundation for several rights-based decisions, including:

- Navtej Singh Johar v. UOI (2018) – Decriminalized homosexuality (Section 377 IPC)

- Joseph Shine v. UOI (2018) – Decriminalized adultery (Section 497 IPC)

- Common Cause v. UOI (2018) – Recognised passive euthanasia and living wills

- Puttaswamy-II (2018) – Upheld Aadhaar in part but struck down several coercive provisions

🔒 2. Data Protection and Tech Governance

Inspired the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019, and later the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023

Sparked corporate accountability for data leaks, profiling, and consent violations

🌏 3. Global Influence

- Cited internationally in debates on surveillance capitalism, AI regulation, and facial recognition systems

- Showed how a Global South country can lead in defining digital civil liberties

📚 Key Legal Provisions Involved

- Article Protection Offered Article 21 Right to life and personal liberty Article 19 Freedom of speech, association, movement Article 14 Equality and due process

🧾 Official Citation

Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd.) v. Union of India, (2017) 10 SCC 1

💬 Final Reflection

“Privacy is not a privilege. It is the foundation of freedom, the essence of dignity, and the heartbeat of democracy.”

The Puttaswamy judgment has become the Magna Carta of privacy in India. It empowers every Indian to reclaim their autonomy in a world of Aadhaar, artificial intelligence, and algorithmic control.

This is not just a case about the right to privacy. It's about the right to be human in the digital age.

👩⚖️ About the Author

Dr. Payal Arya Sah is a practising advocate and legal researcher dedicated to advancing constitutional law, data justice, and public welfare. She heads legal outreach initiatives for soldier families and marginalised communities, and writes on key legal transformations in modern India.